Designing the Built Environment to Bridge the History of the Past with the Promise of the Future by Fostering Connections Between Education, Sustainability and Community

Designing or renovating a (K-12) school for an existing community can be as simple as taking the students’ needs into consideration and building a structure that reflects those needs. But some architects like BBS are going further, designing schools in ways that reflect the needs of the greater community and, as a result, the school changes the entire community, not just the students within, for the better. This approach bridges the gap between old and new, past and future, the students and the surrounding community.

CASE STUDY: Hampton Bays Community

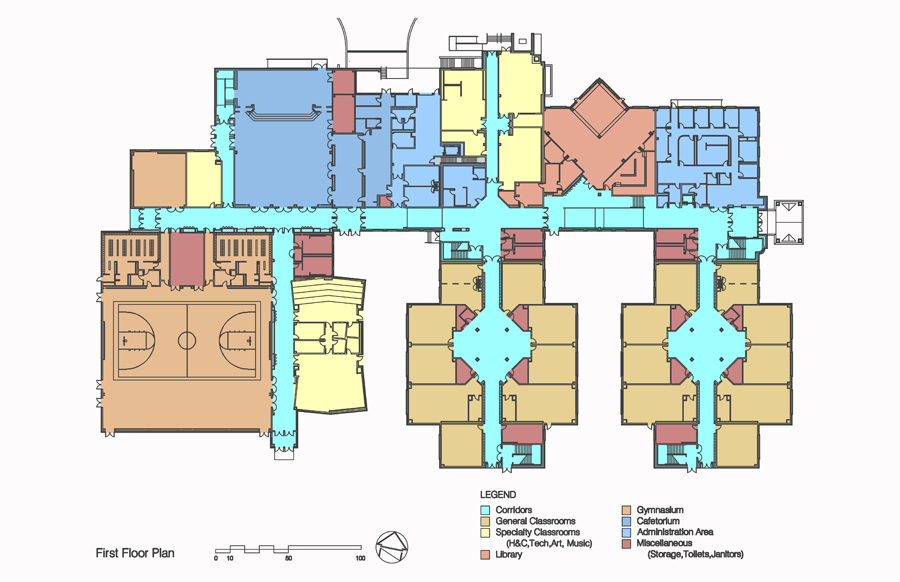

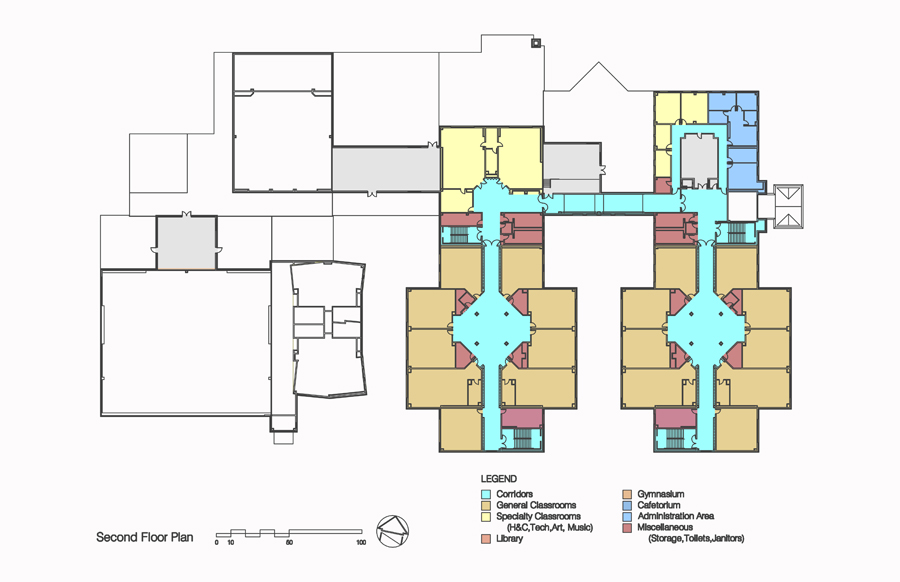

One such example of an entire community positively impacted by its schools is Hampton Bays, New York. Hampton Bays is a hamlet in the Town of Southampton in Suffolk County, Long Island. BBS Architects, Landscape Architects and Engineers, one of the leading (K-12) design practices in the country, was in charge of the design of the brand new Hampton Bays Middle School, completed in 2008. The new $42 million, two-story, 146,400-square-foot middle school is adjacent to the town’s elementary school. It houses 800 students in grades 5 through 8 and features 30 classrooms and lecture rooms, a competition-sized gymnasium with seating for 500, a library/media center, a cafeteria combined with an auditorium and a full theatrical stage, and a home and careers room with six fully equipped kitchen stations. The outdoor sports facilities include fields for field hockey, soccer, softball, and football- for use by the school and its community.

In the early 2000s, the existing Hampton Bays elementary school was occupied at 155% capacity and the secondary school was occupied at 135% capacity. Moreover, a steadily increasing enrollment was projected for the next several years. The district purchased parcels of land adjacent to the elementary school for future development and BBS used community input to design the new middle school. The design incorporated local maritime landmarks, in particular the beloved Shinnecock Bay Lighthouse, which had been demolished in 1948. The inclusion of this local landmark helped finalize the local voters’ approval for financing the new middle school by reinforcing the importance and impact of this community project.

The Hampton Bays Middle School is not just a more spacious learning environment for students. It is a place where the community at large is embraced as well. The middle school’s traditional academic program is supplemented with rich co-curricular offerings that address varying interests, ability levels, and talents. Cutting-edge technology and media systems are in every classroom. The school also holds community functions, such as meetings, evening classes for adults, multigenerational events, sporting activities, and it even features a community garden that both students and community members use. The school itself is designed a series of grade-level houses, each with its own commons area. The houses are arranged along a “Main Street” that connects them to special classrooms, library, cafetorium, music, etc.

Roger P. Smith, AIA, LEED AP, is BBS’ Principal and the lead architect for the Hampton Bays Middle School. According to Smith, designing (K-12) facilities in this way “can dramatically alter a community and change how it functions.” He says, “We aim to change the way education is delivered, change the way the environment looks and the way the community sees it. The community, in turn, says, ‘Wow, look what we own!’” Smith continues, “We named this the ‘bridge’ planning and design approach – the term that encompasses bridging and accommodating varied needs of the community and its residents of all ages – educational, recreational, social, political, and other.”

While the middle school was completed in 2008, BBS’ work at the Hampton Bays School District is ongoing and in keeping with the “bridge” concept. All work is done with an eye to community inclusion, while upgrading older infrastructure to current technology and sustainability standards. Hence, a $16-million bond funding improvements across the district led to 64 discrete projects, including all new windows on the older buildings for safety and energy efficiency and a new multifunctional library at the elementary school. The work has continued to bridge the gap between the schools and the community.

According to Hampton Bays Superintendent Lars Clemensen, “BBS talks not just bricks and mortar but programmatic and community goals.” Indeed, Smith says that for every project at Hampton Bays, they ask themselves, “Can this space be adaptable to other purposes so the public can experience it, too? We have adult education classrooms that don’t feel like middle school or high school science classrooms. The layouts have to be designed in a way that accommodates the entire community,” says Smith.

This provides long-term benefits beyond the academic. Clemensen said that since the middle school was built there has been a “consistently growing confidence” in Hampton Bays academics. “There’s curb appeal,” he says. “It’s a state-of-the-art facility that looks really good. So it’s easy for people to make the jump that what’s going on inside is good, too.” One need only look at voter approval of school budgets. Back in the early 2000s the average approval rating was 51–52%; currently, it averages 75–78%. Clemensen calls it a correlation of a number of factors, “But the curb appeal is definitely one of them.”

The Hampton Bays Middle School is also a winner of the U.S. Department of Education’s Green Ribbon Schools Program and the first LEED-certified public school in New York State. (It obtained a LEED NC 2.1 Silver rating in 2008.) The Green Ribbon Schools Program is part of a larger effort to identify and disseminate knowledge about practices proven to result in improved student engagement, academic achievement, graduation rates, and workforce preparedness. The middle school is also the first Collaborative for High Performance Schools (CHPS)–certified school in the state. CHPS is a national organization that promotes the design and operation of healthy and resource-efficient educational facilities.

The green aspect is not merely a part of the design, it is part of the curriculum. The school has incorporated environmental awareness into its course offerings, including composting and gardening. Clemensen described a green technology class in the 7th and 8th grades, a building-wide earth club, and a robotics elective that has embraced sustainable components. Green design impacts both students and adult community members. As many as 30 students take care of a garden bed adjacent to the Middle School and 30 local community members rent space as well. The gardens of students and adults grow side by side.

Clemensen notes that Hampton Bays has no town hall, so the schools have begun to serve as a community center. The multigenerational interaction that this provides promotes tolerance. “You have a lot fewer adults wagging fingers at kids today, in part because they’re attending functions together,” he says. Whereas once school buildings had to close on election days due to a lack of parking spots and voting spaces, now the middle school remains open. “Residents are seeing kids in action and seeing the school living and breathing,” Clemensen continues. “A strong education system is the first step in making the community better. We’ve seen median home values increase and home inventory has been moving.”

CASE STUDY: Riverhead Community

Riverhead is another Long Island community in which the BBS bridge concept has taken hold. The recently completed $78.2-million, multi-year Riverhead Central School District expansion and capital improvement program encompassed five elementary schools, one middle and one high school, as well as the main campus site. “By improving and expanding schools built between the 1930s and the 1960s, we’ve created a secondary downtown,” says Smith. “Our work in the schools was a catalyst to the community building phenomenal restaurants, and shopping and entertainment venues in an area that was formerly a sleepy crossroads passed on the way to the Hamptons or the wineries of North Fork. We can change these kids’ lives and the lives of all who go to see a play or basketball game in the school. It gives them a sense of pride, a sense of ownership, a sense of community. We’ve bridged to something different. It’s symbiotic. We’ve helped weave together this formerly fragmented community.”

Embracing the Past to Provide for Future Generations

When renovating or adding to an older, even historical structure, BBS believes the existing structure must be embraced. This not only means preserving the existing structure, but creating an addition that complements the existing building. The older school structures often hold a strong emotional connection to the generations of parents and grandparents who attended them. Preserving these buildings helps maintain the continuity of the educational experiences throughout families and neighborhoods. “We’re not afraid to architecturally replicate what’s there during expansions and renovations. Our goal is to keep older generations engaged and invested in the success of each following generation of students. Maintaining the architectural continuity of older schools helps achieve this objective,” said Smith. He simply makes sure the programmatic use is forward-thinking and encompasses the educational needs of the entire population.

Long Island, and the northeast in general, is leading the way – bridging old and new, present and future. After all, most of the communities have been “built-out” for many decades already. “In rapidly growing southern Virginia, for example, this would be very different. They’d be creating the entire neighborhood. Here in New York you’re going into an established neighborhood that’s been there for 100 or even 200 years and you have to try to position the school in such a way that it’s going to be relevant 50 or 100 years from now. This is a bigger challenge.”

Encompassing the community’s needs as an integral part of the architectural approach to (K-12) facilities is a part of the new wave in educational planning. The bridge concept is the present – and future – of (K-12) design. As Smith says, “It’s proven that quality environments improve education and improve grade scores. First and foremost, as an architect, you have to embrace the idea that you are truly responsible for the betterment of children – and the community as a whole.” Designs follow intent; buildings become the physical manifestation of the design process, and enhanced student and community experiences become the ultimate result.